Even when nobody involved has bad intentions, learning about foreign cultures from a distance can be problematic. For example, if you want to know about the land of Boogleboopy–and you can’t go and emerge yourself in the Boogleboopite culture–you’ll have to rely on reports from others. In fact, most of the world’s people don’t go abroad, so their knowlege of other cultures has to come from what is reported to them.

What can go wrong? A lot. The informant may think he’s gotten a bead on the foreign culture when really he hasn’t. When he’s in Booglyboopy, he’s served popiba berries with every meal. He goes back to his homeland and tells his buddy, “Boogleboopites eat popiba berries with every meal.” Actually Boogleboopites only eat popiba berries on special occasions (weddings, the birth of a child . . . and when a visitor arrives from abroad). Or he might say something that is absolutely true, but say it in a way that makes his buddy back home misconstrue the information. “I was invited over for dinner by seven different Boogleboopite families–and every time they had an enormous bowl of popiba berries on the table. Man, do they love their popiba berries!” The informant doesn’t say popiba berries are a daily staple, but his homeland buddy may mistakingly infer that they are.

The informant, of course, cannot paint one hundred percent of the picture, no matter how accurately he tries to report, so much of what Boogleboopites are really like will have to be left up to his buddy’s imagination–and with no experience of any foreign culture, that is, with his own culture having to serve as the default when information about the remote place is lacking, he might come to some mistaken conclusions.

At least he might every now and then. . . . And it’s possible he might a great deal of the time.

One of the best illustrations (literally, illustrations) of this principle is a children’s picture book, written and illustrated by Leo Lionni, Fish is Fish (1970)–a wonderful book.

In a pond, a fish and tadpole become friends. But then the tadpole becomes a frog. He leaves the pond. He goes “about the world–hopping here and there”–and sees “extraordinary things.” He comes back to the pond. He tells the fish of all he’s seen. Birds, cows, people.

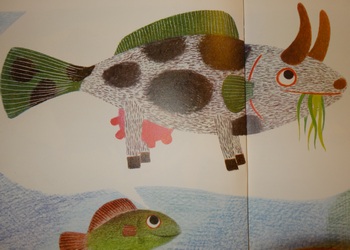

“Cows,” said the frog. “Cows! They have four legs, horns, eat grass, and carry pink bags of milk.”

What the frog says is one hundred percent correct, but the fish is incapable of imagining anything he’s not explicitly told. The frog has assumed, wrongly, that his buddy will be able to infer all the physical attributes of a cow from a description of only three. And so the fish imagines a creature just like himself, a FISH (that is, a long, svelte creature with fins) . . . only his long, skinny, finned fish has four legs, horns, and pink bags of milk, and it eats grass.

To the fish’s miraculous credit, he does not, when told that cows “carry pink bags of milk,” imagine his cow carrying them with her hooves! I surely would have. If I could have imagined her hooves!

I wonder if the fish assumed that girl cows and boy cows both carry milk. I wonder if he thought that strapping pink bags to your belly and stuffing them with milk was a bit daft. Wouldn’t he have thought you should keep stuff like that in a cooler place, like, say, the bottom of a pond?

I love this book–and highly recommend it to all the children and adults out there, and especially for all the cross-cultural-understanding educators and students out there.

When you read, of course, its very important to realize that neither the frog nor the fish has bad intentions. And it’s also important to realize that neither the frog (the informant) nor the fish (the stay-at-home buddy) is aware that the frog’s images of birds and cows and people are at all off the mark. The fish thinks he’s got it. The frog thinks he’s given it to him.

Near the end of the story, the fish decides to see the amazing world for himself. Alas, a mere few seconds of flopping about on the grass at the edge of his pond convince him that he was not meant to be a world traveler. He’s left to conclude that his world–the pond–is “surely the most beautiful of all worlds.”

Of course he does! And no doubt, for him, it is the most beautiful.