Warning: there’s a song, an audio track, at the end of this brief musing. But if you prefer a song over prose, by all means, skip right down to the song.

It seems many of us are wondering what exactly this period of coronavirus is good for. Of course, it is a time when we must do all we can to stop the spread of the virus, and to find ways to treat the sick, and to figure out ways to help those whose economic/educational/working/social-interacting/emotional selves have been put in jeapordy as a result of the pandemic.

But beyond that, what to do? Some seem to think it’s a good time to inject a healthy dose of humor into our lives—that that will ease our anxieties. Others are saying how it’s a time to let art and music wash over and soothe us. And yet others seem to think (especially those of us prone to contemplation) that a time of disruption is a time to re-think who exactly we are, we living human beings, and what exactly we’re all about.

I think everyone is more or less right.

If there’s one thing the pandemic makes clear, it’s that there is really no way we can separate us from them. The virus knows no borders. We are all in the same single environment. And we are all vulnerable.

It’s natural to want to be less vulnerable, but an obsessive struggle for invulnerability is true madness.

I disagree with many things that David Brooks, The New York Times columnist, has to say, but I almost always agree with a part of what he says. His March 19th column is no exception. He is so right when he writes, “Don’t expect life to be predictable or fair. Don’t try to tame the situation with some feel-good lie or confident prediction. Embrace the uncertainty of this whole life-or-death deal. There’s a weird clarity that comes with that embrace. There is a humility that comes with realizing you’re not the glorious plans you made for your life. When the plans are upset, there’s a quieter and better you beneath them.”

“We’re all going through the same experiences,” he continues. “People in Seoul, Milan and New Jersey are connected by a virus that reminds us of the fundamental fact of human interdependence.”

Interdendence. Yes, to me, this tough, tough time of coronavirus is a good time to think about whether it really is possible to think about a world/universe in which it’s possible to ever be separate from anyone else—or for that matter, anything else.

The following may sound obsessively pedantic, but I don’t think it is at all: A man sits in a chair. He breathes. Air comes into his lungs. Deep in his lungs, oxygen is taken into his bloodstream. Oxygen is delivered to all his cells. In this process, where exactly can you draw the line between him, the person, and his supply of air? If you were pushed, I’m not sure that you could. But even if you insisted that the man and his air supply are different, where exactly would you draw the borders around his supply of air? Could you do that? I don’t think you could. And there would be a hell of a lot of trees all across the globe contributing to that air supply. And there would be all sorts of beings here and there relying on those trees.

And so on.

Personally, it’s hard for me to imagine that there could be any doubt about our inseparability, and I would have thought that if there were such a doubt, global climate change would have destroyed it. Apparently, though, it hasn’t.

There is one world. We are all one. That’s really all there is to it.

But I know that some folks don’t think so. One of my favorite books for young people is Stargirl, by Jerry Spinelli. This has one great scene which presents the different ways of thinking very clearly and concisely. The hero, Leo, a high school student, is madly in love with Stargirl, an outsider, an individual thinker. He loves her because she is “different,” but is irritated in his daily relationship with her because she is different. He thinks that both she and they (the couple) would be better off if she would just recognize the need to follow the ways of his high school clan. He certainly believes in separability. If she would just recognize that there is both an inside the group and an outside the group, everything would be better.

“This group thing, I [Leo] said, it’s very strong. It’s probably an instinct. You find it everywhere, from little groups like families, to really big ones like a whole country. How about really, really big ones, she [Stargirl] said, like a planet? Whatever, I said. The point is, in a group everybody acts pretty much the same, that’s kind of how the group holds itself together. Everybody? she said. Well, mostly, I said. That’s what jails and mental hospitals are for, to keep it that way. You think I should be in jail? she said. I think you should try to be more like the rest of us, I said.”

We are all one. I think Leo would like to believe it—ultimately, that’s why he’s attracted to Stargirl, the girl who roots for both teams in a high school basketball game—but he just can’t. For him, there has to be an inside and an outside—a duality, and thus he loses the love of his life.

When we divide things into groups, or people into groups, we are doing so for our own convenience, giving them names and categories—to make things easier for us. When we adjust the borders, whether we do so with political, economical, social, religious, humanistic, or even altruistic motivations, we are slicing the world up in ways that seem “good” for us—are to our advantage, you might say. But these slices are not slices that are a natural part of the world, and in making them we tend to commit the sin of thinking that all beyond our man-thought-out borders are somehow less important than we are.

I’m not suggesting that we avoid breaking up into groups, but only that as we do, as we create societies, we remember that we are doing so for practical reasons, selfish reasons, really, and that any temporary slicing we do does not change the fact that this world is one, and that every person alive is our brother or sister.

And let’s hope Leo is wrong about groups. If everyone in a group “acts pretty much the same,” then some of the people are acting pretty much untrue to themselves, because every person has a unique inner nature—an inner nature that must thrive for a person to find life worth living. We don’t need any groups that don’t allow for that.

But for sure, when we refuse to see ourselves as one world, we do tend to see others in a lesser light. We create a strong sense of values within our group, evaluate our group highly—and in so doing, devaluate all that lies outside it.

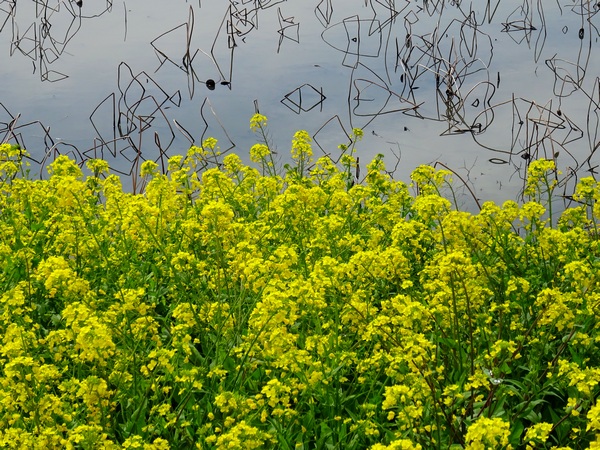

A garden metaphor might be helpful. You and your group want to grow some summer vegetables. You work like hell to cultivate, you plan precisely, you plant and water, but then some other plants that you didn’t anticipate start poking their heads out from the soil. They grow like crazy, faster than the veggies you planted. They take (steal?) nutrients that you’d hoped your veggies would get. What to do? Well, what you do is yell, “WEEEEEDS!!!”—and you go to snuffing them out.

I’m not suggesting that a gardener not snuff out the weeds. I’m just saying that those plants were not created by God, or the mysterious creator, or the magic of the universe, or whatever, as weeds.

You are only designating them as weeds for your own convenience.

And if you can get yourself to accept that fact, well, I think that everything that comes after (whether you ultimately pull up the “weeds” or don’t) is bound to be better—for you and for all.

Yeah, when you get into the habit of watching your thinking carefully like this, you’re much more likely to see things from the points-of-view of the “weeds,” you’re much more likely to feel connected to the oneness, and indeed as Mr. Brooks suggests, this is a feeling to embrace.

It feels so nice in good part because you are being honest about the reality of things.

So here’s a song. It’s got a bit of humor, and hopefully, it will provide something of value musically. And just maybe it will put you in a bit of a contemplative mood, one that somehow proves productive.

I’m Just a Weed

If it suits you fine,

If you really don’t mind,

Please let me be.

I’m just a weed.

Yeah, I’m just a weed.

Uh-huh, I’m just a weed.

Not taking much ground.

Not making much sound.

My throat’s getting dry.

I hope I don’t die.

Oh man, don’t you feel so sorry for weeds

Chased by religion, violence, and poverty

Blown by winds and driven by rain

Sometimes you see one hopping a train.

A seed tip manages to nestle in soil

For a couple of weeks he’s feeling blue royal

But then the man with the weedwhacker comes,

Whacks off his head like he’s one of the bums.

I once knew a girl named Harujion,

I loved her pink color, loved that skin tone,

Her heart and smile like a brilliant sun,

Her shiny silk hair in the breeze such fun.

But then she broke my heart when she said

That soon at the latest all her friends would be dead,

Some pulled up and stuffed into the trash,

Some coldheartedly smothered with gas,

Some shipped into space to fill black holes,

Some blown away in a swirling dust bowl.

She said I know I’m as sweet as any flower,

Got the bees and the June bugs in my power

‘I’m a daisy,’ I lied, ‘just my hair a bit thinner.

‘If you leave me alone I’ll be gone by winter.’

But that man didn’t mind if I thought him a sinner,

He said by tomorrow I’d be burnt to a cinder.

My great grandfather was a dandy fellow,

At peace with all, extremely mellow.

He loved the mountains and rivers and sea

And all the rest that loved to be free.

But then the fescue lawns crowded in

And his dandelion folks began to grow thin.

A single blade of grass got up in his face

Said to be honest I don’t care for your race—

So unless you’ve got affidavits and deeds

A team of lawyers, an irrefutable creed,

Or you get together a big stack of wampum,

The fescue cavalry will come in and stomp you.

’Cause this land you’re on is a fat loose tuna

And it’s up to us to finally harpoon her.

My great grandfather didn’t have much loot

So he strapped all still living into white parachutes.

So now that’s what we do all the time,

We ride air currents and we climb and climb.

We look for a bit of space that can be our castle,

Where we can have quiet, and not any hassle.

And let me tell you what makes me so mad—

It’s the basic fact that we ain’t so bad.

We dandelions are an ethical breed,

So there’s really no need to call us a weed

Potassium, calcium, Vitamins A, B, and C,

That’s the kind of stuff that fills up me.

I make the soil around me soft and clean,

So nobody needs to treat me so mean.

But it’s a beautiful day in early May

And I see the root remover coming our way.

He’s going to rip us out and leave us dry.

And all I can ask is “Why, oh, why?”

I can feel his metal squeezing my ears

And now I’m knowing the worst of my fears

Oh, god, why did you have to do this to me?

Why, oh, why, couldn’t you just let me be?!

(from Persimmon Dreams: When you’ve got a spare moment, check out our music/nature videos on our “Persimmon Dreams” YouTube channel, or Steve’s books, When a Sissy Climbs a Mountain in May and Along the Same Street, available on Amazon, or directly from us. And if you enjoyed this post, consider sharing with others. Thank you!)