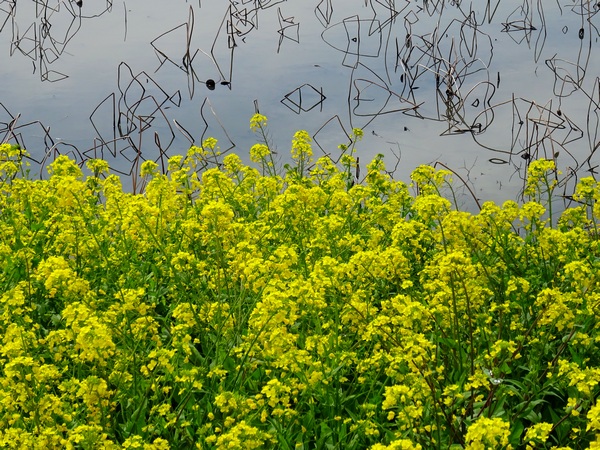

Not far from my house, beside the lotus pond, kawazu cherry trees grow along a walking path. There are more than sixty trees on each side of the path, so it’s a nice little stroll—and a nice stroll. The other day, the trees were in full bloom. The bees were mad with bliss, and the mejiro, too, were caught up in the heavenly harvest. The mejiro—green bodies, white rings around their eyes, smaller than our local sparrows—flit from branch to branch, hopped from blossom to blossom, contorting their bodies in whatever way necessary to position their beaks for a straight jab down into the cherry nectar.

Suddenly I smiled. I remembered something I’d overheard a while back. Two women were discussing cooking, in particular how to deal with a recipe that called for “a whole chicken.” One of the women said that she only bought pre-cut breast meat—and was “grossed out” if she had to slice it up. I assume that she meant “before she cooked it.” The other responded by saying, “My mama could cut up a chicken.”

I wasn’t listening all that carefully, so I might have missed an important segment of the conversation, and just maybe I misinterpreted the second woman’s intonation. It’s possible that she meant, “My mama was better than anyone I’ve ever seen when it came to cutting up a chicken.”

But what I actually heard was this: “My mama could cut up a chicken. I don’t know how, but she could. I wouldn’t have the slightest idea how to go about it.”

And I thought that if we have come to think that cutting up a chicken is some miraculous ability that we as fully developed and elite animals are no longer capable of (have gratefully outgrown, some might say), we are in serious trouble. If we have come to believe that unquestionably doable things are in fact undoable, then we truly are lost.

And that’s why it’s important (even if you choose to purchase pre-sliced, skinless chicken breast) to know that you can cut up a whole chicken.

You may not have the instinct a mejiro does, but your fingers are not made in such a way that they cannot learn to use a knife, and with a bit of practice, a bit of trial and error, you can indeed become a chicken cutter-upper par excellence. After a while, if you do choose to become a cutter-upper, it might feel like something you have an instinct for—at least something you can do easily and well and with clear purpose.

Regardless, it’s nice to learn how to do things you’ve always thought you couldn’t. To develop an instinctual feel for a particular task. To surprise yourself with what you, a single individual, are capable of.

In this age of specialization, we are much less likely to be doing something completely by ourselves than folks were hundreds of years ago. We are more likely to be a part of a system, a system whose processes and purposes we cannot always control.

Nope, I’m not against teamwork, not against pooling talents. But there can be a negative side to joining a team you can’t quit, a negative side to relinquishing control over what you want your efforts to achieve.

So, for what it’s worth, here’s how to cut up a whole chicken:

Get a good knife. Place the chicken, breast up, on a good cutting surface. Slice into the skin between the legs and the body. Feel for the joint. Pull on the leg, pop the leg bone out of the joint, then cut the leg off completely. Following the fat line, cut the thigh from the drumstick. Feel for the middle of the joint, as necessary. Repeat with the other leg. Slice the skin between the wing and breasts, feel for the joint, and cut on through. Repeat. Identify the fat lines running between the backbone and the breast. Cut. Keep cutting through the ribs. Some people like to use scissors for this part. Put the backbone and attached meat in your soup pot. Place the remaining double-breast skin-side down. Cut into the little bone in the middle of the double-breast. Flip the breast. With the palm of your hand break the breastbone. Cut the breast in half.

Finished.

In Walden, Thoreau wrote, “[M]an’s capacities have never been measured; nor are we to judge of what he can do by any precedents, so little has been tried.”

That’s so true. So little has been tried.

When I was small, people used to say, “Can’t never could do anything.” I no longer live in an English-speaking country. I don’t know if they still say that or not. But I hope they do.

Surely they do. And we should listen. Because we are capable of so many things.

(from Persimmon Dreams: When you’ve got a spare moment, check out our music/nature videos on our “Persimmon Dreams” YouTube channel, or Steve’s books, When a Sissy Climbs a Mountain in May and Along the Same Street, available on Amazon, or directly from us. And if you enjoyed this post, consider sharing with others. Thank you!)