The lily blooming in my tiny backyard garden may not look particularly special. After all . . .

. . . these guys are blooming all over town—and in abundance. But the one in my garden has a history. Back in February I was driving home. I’d just been in a real estate agent’s unnecessarily plush office signing a contract, buying a seventy-some-odd tsubo plot of land in the northern part of the city, a neighborhood—Kita (literally, “North”)—nestled between two long rows of little mountains. The plush office, along with the free packages of, yes, wait for it, saran wrap, were just a little too much.

Together, they got mind typhooning. Oh, a tsubo = 3.3 square meters.

So there I was, in the car driving home, and I say to the hearty hiker who was with me, “I don’t feel like I just bought a piece of land. I mean, someone can’t just sell you a piece of land, can he? You can’t really buy land, can you? Can you?”

“No, not really,” she replies.

“Right? I’m right, right?”

“Of course.”

“Okay, I feel better. You want to go by there?”

“You had better. If you’re going to knock down some trees, you’ll have to tell them. They’ve got a right to know their fate.”

“Exactly.”

There was an old house to be knocked down, but that didn’t bother me at all. It was the plants. I had a plan for a garden, new soil was going to have to be brought in, and the plants living there happily weren’t, unfortunately, for the most part, going to be able to stay.

Were some guy to rush the property, drive a stake into the dirt, claim it for himself, start construction on a hamburger joint . . . I would call the police. That’s what legal ownership means, I guess.

But the plants aren’t interested in that.

We thanked them for making way for us. (My house it will be, I suppose, but members of the Hearty Hikers are welcome to stay whenever they like. Heck, they can move in if they want. I love those guys.)

We told the plants we’d take care to take good care of the energy of the place.

We couldn’t save them all, but I dug up a kane-no-naru plant (a “money-making” plant, so called perhaps, because the leaves resemble coins (however, slightly), and maybe called a “dollar plant” in English). And the lily. I didn’t even know that it was a lily at the time. It wasn’t very big.

And the camellias were getting ready to bloom. I clipped some buds and took them home.

Then we walked to the neighborhood shrine.

February, right. The plum blossoms were lovely.

The altar was shining.

“They know who you are,” my HH buddy said. “They’re happy to see you.”

I explained to them who I was. I’m moving in, just up the hill, I said, head bowed. Gonna make some noise knocking down the old house, putting up a new one. I hope that doesn’t bother you guys too much. I’m aware of the energy up there. I’ll try not to do any damage to it. I promise I’ll do my best not to mess it up.

I felt pretty good walking back to the lot. I’m guessing I didn’t make such a bad impression.

But you can’t just do this once and think you’ve got eternal license. You’ve got to do it every day—and even then your license will be eternally limited. You’ve paid for stewardship, and nothing more.

May 31. Groundbreaking.

The sky is blue. Two priests are dressed in a deep bluish-purple. They explain what’s going to happen. Basically, we’re going to let the local deities know, again, what we’re up to. Ask for understanding. First, though, we need to clean up a bit.

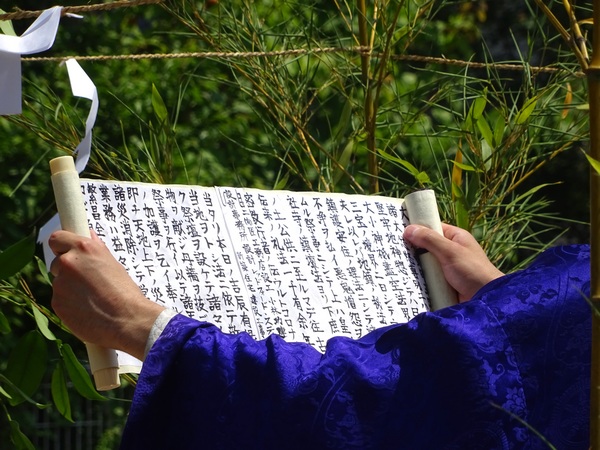

The priests take turns chant-chant-chanting. The older one is 88. I figure he must know the dieties pretty well. The young one chants while reading from a scroll.

The chanting goes on for quite a while. Sometimes words leap out clearly—Mr. R would like to build a house here . . . no fires, please . . . bless the plans of Mr. Architect . . . don’t let the heat bear down to hard on the carpenters employed by Mr. Builder—but a lot of it is just ruh-ruh-ruh-ruh-ruh-ruuuuuhhh, ruh-ruh-ruh-ruh-ruh-ruuuuuhhh, ruh-ruh-ruh-ruh-ruh-ruuuuuhhh.

I loved that sound. I could have listened all day—listened all through the night.

The chanting flows into you, like the vibration of your ukulele. Those few words that you can make sense of have popped out from the chanting so comically that you are certain they have done so to remind you how comic your existence is—No! You DON’T own this land!

And then the young priest blows on a big conch shell! It’s huge and he puts everything he’s got into it, and you think that maybe he’ll knock the sun right out of the sky, but the sound comes out all muffled, and it’s as off key as it can get, but still it’s so full of expression, so sincere, so humble, that you suddenly turn to—who else?—yourself and say: Utatte ii!

That is . . . “You can sing! There’s no reason not to sing! You should sing!”

You want to fly home, grab your ukulele, fly back. You want to stand in front of that shrine, bang away on those four strings and sing, “Wa-wa-wa-wa-wa-wa-wa-wah, ba-ba-bloo-ba-bing-bang-boo.”

The crows are circling now, cawing. They’re spreading the word: “Hey, this R guy is here. He’s building. Seems all right. Let’s give him a chance.”

And then the cups of sake are offered. We drink a little, too.

And then I take a hoe and slice down the ceremonial mountain of dirt.

Let the fun begin.

The lily blooms.