What sort of problem is it when you can’t afford to live in the part of town where no one has any garden space, your home is not surrounded by luscious green mountains, and there is no lotus pond just down the road?

It’s the sort of problem I can live with.

There’s the pond. There’s Ryuso Mountain. I’m lucky to live somewhere in between.

But you’re not too far away from the pond anywhere in Shizuoka. And you can always book a place on the mystery tour.

June and July are the big months for the pond. A few weeks back, though, when the blossoms were opening over about half the pond, we had a torrential rain. The dark gray clay of the pond is just like the dark gray clay of the rice fields. It holds water. The lotus leaves, which rise a good four feet above the surface were all submerged and the blossoms that had opened were destroyed.

A lot of the leaves died–or half died.

Now, at least over a lot of the pond, the buds are reappearing, and new blossoms are opening again. The buds that haven’t opened, well . . .

. . . some folks just can’t seem to wait for them to.

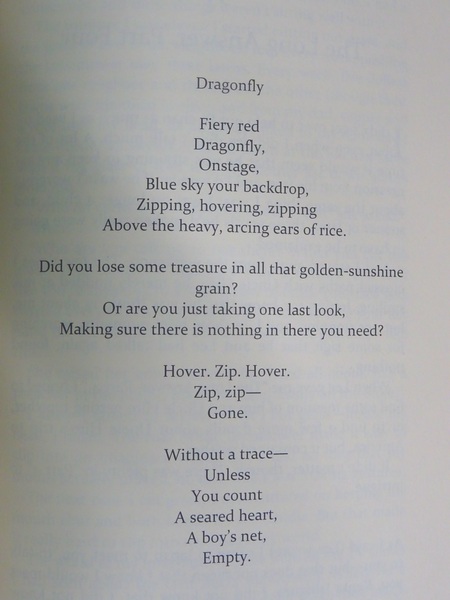

A few years ago, I wrote a novel, Along the Same Street. The protagonist, Kenta, a teenage boy, wrote a poem about a dragonfly. In his mind, an autumn rice field was where you’d go to try to catch a dragonfly. For him, a dragonfly was a metaphor for the amazing girl he loved. And he tried to make his poem look like a dragonfly.

The dragonflies I saw at the pond were not so frenetic.

One seemed content to perch on a not yet unfolded lotus leaf—and remain there.

The other on the bud.

Well, you’ve gone to see the blossoms, but you end up watching the dragonflies.

And then you notice the damselflies.

You might not have even known that there was such a creature as a damselfly. And you might even get to see a pair make love, see them clasp onto to each other and curl their abdomens, forming a heart. It wouldn’t be at all strange if you saw that—because that’s why they’ve taken on their adult forms—and they’re only going to live as adults for a few weeks.

Yeah, but just sit and watch the dragonfly sitting on the lotus flower.

Maybe think about the leaves of the lotus. They’ve got a special surface. Just as birds’ feathers do. Water rolls off them. Or rolls into them. Yeah, first it rolls in, collecting whatever debris that has fallen into the leaf, then the leaf grows heavy and tips over—and . . .

. . . Presto! You have a perfectly clean leaf!

At the lotus pond, watching the dragonfly (My! but he looks obsessed with that bud!), you might began to wonder about yourself. You’ve slowed down. You’ve got the time.

You might wonder what you were meant to do all day every day. Might wonder, over the long haul, what you were meant to get done.

You might wonder what legacy you’ll leave behind when after your petals have fallen . . .

. . . after your bones have gone bare.

They say that a lotus seed can sleep for several thousands of years and then germinate. If you’d like to ensure that a message of love and beauty and truth survives deep into the future . . .

. . . you could do worse than leave behind a single lotus seed.

Things don’t always go as planned.

But an inner nature, if allowed, usually can find its way to the light.

That’s what beauty is—an inner nature, allowed, finding its way to the light.