The last day of May and I was back on the trail up Yambushi. The two or three days before, I’d been feeling worn down (legs tired), but somehow once I started the climb, I felt refreshed and did the whole walk at a brisker pace than normal, a little over four hours up and down, including a 20-minute break at the top, five minutes for snake observation, and the time it took to take 130 pics.

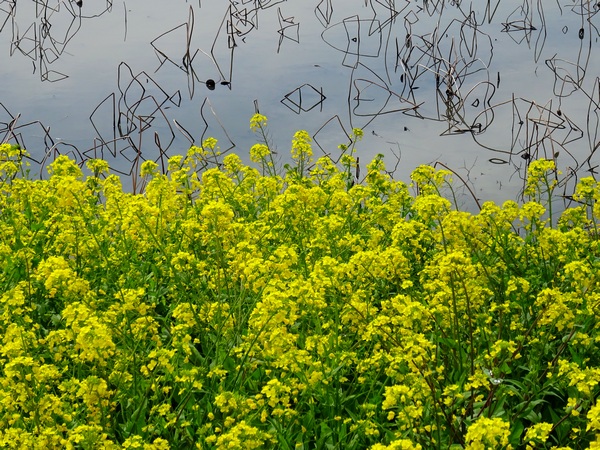

Maybe it was the oh-kin-kei-giku I met on the drive up. The pic above could be titled “On the Road to Umegashima,” but also “What it looks like in my mind when I’m on the road to Umegashima.”

The hike up Yambushi follows the Nishihikage Creek up to the Yomogi Pass, then wanders waterless through the woods to the top of Yambushi. In all, it’s a rise in altitude of about 1200 m over a trail distance of 4.3 km–a fairly steep go.

Recently, like almost all other teachers all over the world, I’ve been struggling with online classes, trying my best to give every student the best experience I can. One assignment I gave my first-year university students in my “English Communication” class was to interview me, via video-conferencing, on any topic they liked, and then to produce a “newspaper feature,” based on the interview, so that I could encourage both their speaking and writing abilities. The students had heard me say I like hiking, so unsurprisingly, not a few of them decided to focus their interviews on my hiking experience—and most of those asked me, again unsurprisingly, “Why do you like hiking?”

So as I hiked up Yambushi, I began thinking about that question myself. Thinking about that question again.But it’s all pretty simple.

1. Hiking (walking) is good for health, especially when it requires a bit of exertion. (But it doesn’t have to be exhausting. You shouldn’t have to gasp for breathe. In fact, you shouldn’t gasp for breathe.)

2. Hiking is good for breathing, and good breathing is good for your soul. Good breathing relaxes. Good breathing makes you feel how alive you indeed are.

3. Breathing well and feeling alive makes your mind work better. You feel creative. You see things in ways you haven’t before. The words to explain a vague conception you’ve “kind of” had suddenly come to you. (And I’m surely not explaining as well as I could if I were still on the mountain walking!)

4. If you are hiking with someone, it suddenly becomes easier to talk. Not just easier to “chat,” but rather, easier, to open your heart. This is because you’ve left behind (however temporarily), the society of human beings–a place where (at least to some degree, you make the judgement), lies and ego and selfishness exist. None of those things exist on the side of a mountain. On the side of a mountain, walking, you feel less afraid to open your heart to others—or so it has seemed to me.

5. If you are really breathing well, you begin to feel as if you are not just breathing in from the cubic meter of air most immediate to your face . . . but breathing in the all the air up through the treetops and beyond—you may even feel as if you are breathing in the whole mountain, the dirt beneath your feet, all the trees, and more or less, all the universe. It’s possible, if you’re breathing well, to realize that you are the universe and to feel you are the universe. And that is a pretty good thing. Here, I’m reminded of the passage from J.D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey, in which Franny is trying to explain to her boyfriend Lane what it means to pray without ceasing. In my mind, Franny’s “praying without ceasing” is fairly synonomous with both my “walking” and my “breathing.”

… if you keep saying that prayer over and over again — you only have to just do it with your LIPS at first — then eventually what happens, the prayer becomes self-active. Something HAPPENS after a while. I don’t know what, but something happens, and the words [breathing] get synchronized with the person’s heartbeats, and they’re actually praying without ceasing. Which has a really tremendous, mystical effect on your whole outlook. I mean that’s the whole POINT of it, more or less. I mean you do it to purify your whole outlook and get an absolutely new conception of what everything’s about. . . . You get to see God.

Franny’s pretty much right, I think. Breathing really well, and just being there in the present . . . well, why don’t you try it yourself, and see how it feels—see what you see.

6. Nature is beautiful. That means, of course, the beauty of the bright spring green leaves and the beauty of the bright blue sky, and the beautiful sound of the river, and the beautiful smell of the river air that makes the breathing beside it so refreshing . . . but it also means, more or less, everything in nature, including mosquitoes, spiders, and those slithering snakes.

Anyway, when I’m absorbed in a walk, and I’m breathing just right, and there is nature all around, I feel all in nature is beautiful. And I like that feeling.

6. When you walk, walk and breathe, walk and breathe in nature, feel the universe, feel you are the universe, the problems that you’ll return to, back down in town, seem less overwhelming—and you can deal with them (live with them? solve them?) with a lot less anxiety.

7. When you are hiking, you almost always see “something new,” even if you’ve already hiked the trail twenty or thirty times. And this is a good thing to experience. To realize how limited your point-of-view often is. To realize how the world is always in flux.

Everything’s changing. Everything’s always changing.

Walking. Breathing. Breathing just right.

To finish up, here’s a short passage from When a Sissy Climbs a Mountain in May.

On the way up, I’d understood about the breathing. I’d felt as if I were inhaling not just the air, but the trees and the sky and the mountain itself, and exhaling all of them, too. Effortlessly. Well, maybe not EFFORTLESSLY, but comfortably, smoothly–the trees hadn’t gotten stuck in my throat going in and out. And for a few seconds–do I dare say this?–I’d felt I held within me, all the good energy of THE ENTIRE UNIVERSE.

And of this I had no doubt: This good energy, once enhaled, has a way of finding the good things inside you, of arousing them. And this is why the Violators can attack you relentlessly for days, weeks, maybe YEARS–and yet you can climb a mountain and remember that you HAVE experienced joy.

So happy hiking!

(from Persimmon Dreams: When you’ve got a spare moment, check out our music/nature videos on our “Persimmon Dreams” YouTube channel, or Steve’s books, When a Sissy Climbs a Mountain in May and Along the Same Street, available on Amazon, or directly from us. And if you enjoyed this post, consider sharing with others. Thank you!)